Memory Layout of Program

06/12/2022 Tags: C_C_plus_plus Embedded Programming“In computing, a code segment, also known as a text segment or simply as text, is a portion of an object file or the corresponding section of the program’s virtual address space that contains executable instructions. The term “segment” comes from the memory segment, which is a historical approach to memory management that has been succeeded by paging. When a program is stored in an object file, the code segment is a part of this file; when the loader places a program into memory so that it may be executed, various memory regions are allocated (in particular, as pages), corresponding to both the segments in the object files and to segments only needed at run time.”

Brief

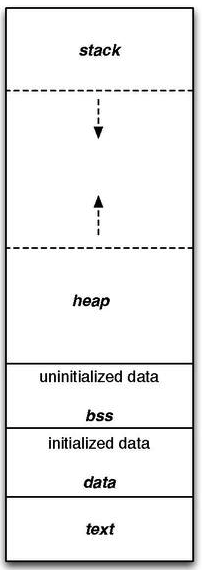

When we declare a variable in program, C++ allocates space for that variable from one of several memory regions: One region of memory is reserved for variable that persist throughout the lifetime of the program, such as constant. This information is called static data. One region of memory is reserved for allocating a new block of memory called a stack frame to hold its local variables. This information is called stack. One region of memory is reserved for allocating memory dynamically. This space comes from a pool of memory called the heap.

In this blog post, I would like to discuss the typical layout of a simple computer’s program memory.

Typical Code Segment

The typical layout of a simple computer’s program memory is with the text, various data, and stack and heap sections.

-

Text section: contains executable instructions and is sharable so that only a single copy needs to be in memory for frequently executed programs. It is often read-only and may be placed below the heap or stack in order to prevent heaps and stack overflows from overwriting it.

- Data section: divided into two parts

-

Initialized Data Segment: contains the global variables and static variables that are initialized by the programmer . It is not read-only since the values of the variables can be altered at run time.

-

Uninitialized Data Segment: often called the “bss” segment and is initialized by the kernel to arithmetic 0 before the program starts executing uninitialized data starts at the end of the data segment . It contains all global variables and static variables that are initialized to zero or do not have explicit initialization in source code.

-

-

Stack section: contains the program stack, a LIFO structure and stores virtual pointer. Each time a recursive function calls itself, a new stack frame is used, so one set of variables doesn’t interfere with the variables from another instance of the function. When the program tries to use more memory space than the call stack has available, it will occur a stack overflow.

- Heap section: managed by malloc, realloc, and free, which may use the brk and sbrk system calls to adjust its size. (brk, sbrk – change data segment size). It is shared by all shared libraries and dynamically loaded modules in a process.

<Remark> An industry group led by major Japanese central processing unit (CPU) manufacturers have addressed the shortcomings of C++ for embedded applications: While maximizing execution efficiency and making compiler construction simpler, the effort of programming is to preserve the most useful object-oriented features of the C++ language yet minimize code size.

Examples of Memory Layout of objects (MAC OS)

- Check the following simple program

simple.c

int main(void)

{

return 0;

}Display summaries of the headers for each section:

$ objdump -h container

container: file format mach-o 64-bit x86-64

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA Type

0 __text 0000000f 0000000100003fa0 TEXT

1 __unwind_info 00000048 0000000100003fb0 DATA

- Check the following simple program with one uninitialized global variable

simple_uninitialized.c

int global; /* Uninitialized variable stored in bss*/

int main(void)

{

return 0;

}Display summaries of the headers for each section:

$ objdump -h container

container: file format mach-o 64-bit x86-64

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA Type

0 __text 0000000f 0000000100003fa0 TEXT

1 __unwind_info 00000048 0000000100003fb0 DATA

2 __common 00000004 0000000100004000 BSS

- Check the following simple program with one uninitialized global variable and one uninitialized static variable

simple_uninitialized_static.c

int global; /* Uninitialized variable stored in bss*/

int main(void)

{

static int i; /* Uninitialized static variable stored in bss */

return 0;

}Display summaries of the headers for each section:

$ objdump -h container

container: file format mach-o 64-bit x86-64

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA Type

0 __text 0000000f 0000000100003fa0 TEXT

1 __unwind_info 00000048 0000000100003fb0 DATA

2 __common 00000004 0000000100004000 BSS

3 __bss 00000004 0000000100004004 BSS

- Check the following simple program with one initialized global variable and one uninitialized static variable

simple_initialized.c

int global 10; /* Initialized variable stored in DATA*/

int main(void)

{

static int i; /* Uninitialized static variable stored in bss */

return 0;

}Display summaries of the headers for each section:

$ objdump -h container

container: file format mach-o 64-bit x86-64

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA Type

0 __text 0000000f 0000000100003fa0 TEXT

1 __unwind_info 00000048 0000000100003fb0 DATA

2 __data 00000004 0000000100004000 DATA

3 __bss 00000004 0000000100004004 BSS

- Check the following simple program with one initialized global variable and one initialized static variable

simple_initialized_static.c

int global = 10; /* Initialized variable stored in DATA*/

int main(void)

{

static int i = 1; /* Initialized static variable stored in DATA */

return 0;

}Display summaries of the headers for each section:

$ objdump -h container

container: file format mach-o 64-bit x86-64

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA Type

0 __text 0000000f 0000000100003fa0 TEXT

1 __unwind_info 00000048 0000000100003fb0 DATA

Inherently Nonportable Features - Bit-Fields

To support low-level programming, C++ defines some features that are inherently nonportable. A nonprotable feature is one that is machine specific. Programs that use nonprotable features often require reporgramming when use nonprotable features often require reporgramming when they are moved from one machine to another. The fact that the size of the arithmetic types vary across machines is one such nonportable feature that we have already used.

A class can define a (nonstatic) data member as a bit-field. A bit-field holds a specified number a bits. Bit-fields are normally used when a program needs to pass binary data to another program or to a hardware device, thus the memory layout of a bit-field is machine dependent.

bit_fields.h

typedef unsigned int Bit;

class File {

Bit mode: 2; // mode has 2 bits

Bit modified: 1; // modified has 1 bit

Bit prot_owner: 3; // prot_owner has 3 bits

Bit prot_group: 3; // prot_group has 3 bits

Bit prot_world: 3; // prot_world has 3 bits

// operations and data members of File

public:

enum modes { READ = 01, WRITE = 02, EXECUTE = 03 };

File &open(modes);

void close();

void write();

bool isRead() const;

void setWrite();

};A bit-field is accessed in much the same way as the other data members of a class, and also usually define a set of inline member functions to test and set the value of the bit-field.

bit_fields.cc

void File::write() { modified = 1; // . . . }

void File::close() { if (modified) // . . . save contents }

File &File::open(File::modes m) {

mode |= READ; // set the READ bit by default

// other processing

if (m & WRITE) // if opening READ and WRITE

// processing to open the file in read/write mode

return *this;

}

inline bool File::isRead() const { return mode & READ; }

inline void File::setWrite() { mode |= WRITE; }<Note> A function specified as inline (usually) is expanded “in line” at each call. In general, the inline mechanism is meant to optimize small, straight-line functions that are called frequently. The inline specification is only a request to the compilee, but the compiler may choose to ignore this request.ga

Reference

Thanks for reading! Feel free to leave the comments below or email to me. Any pieces of advice or discussions are always welcome. :)